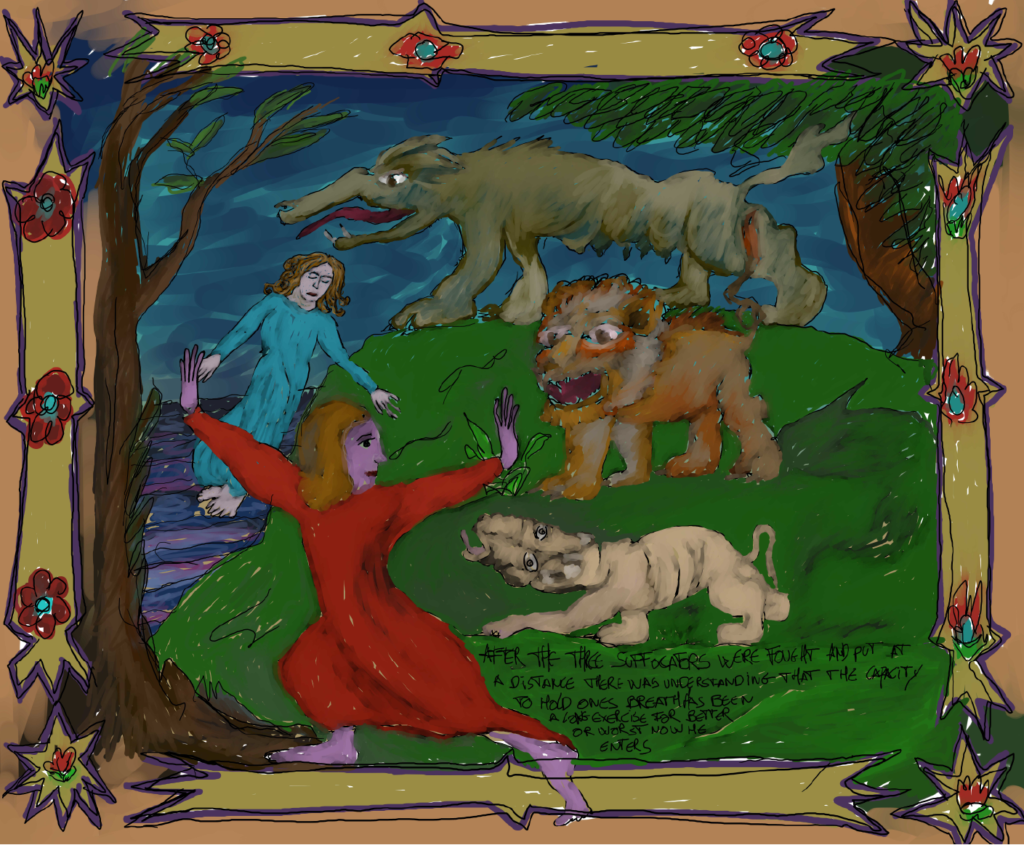

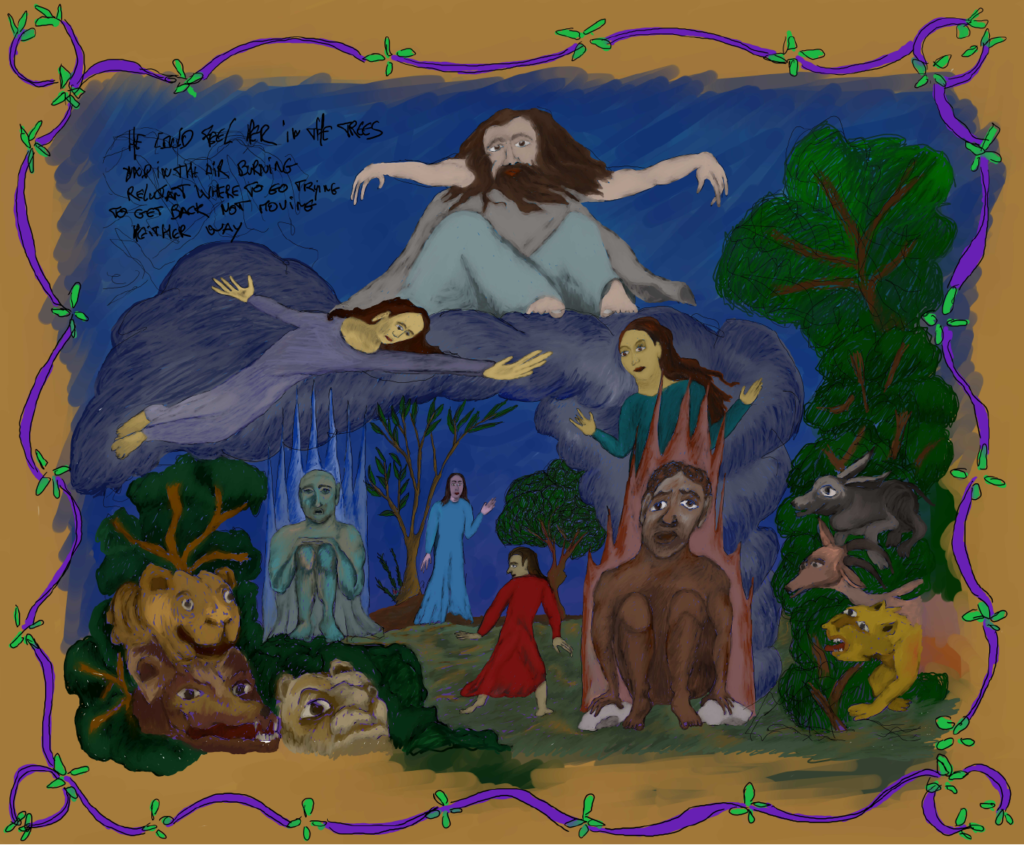

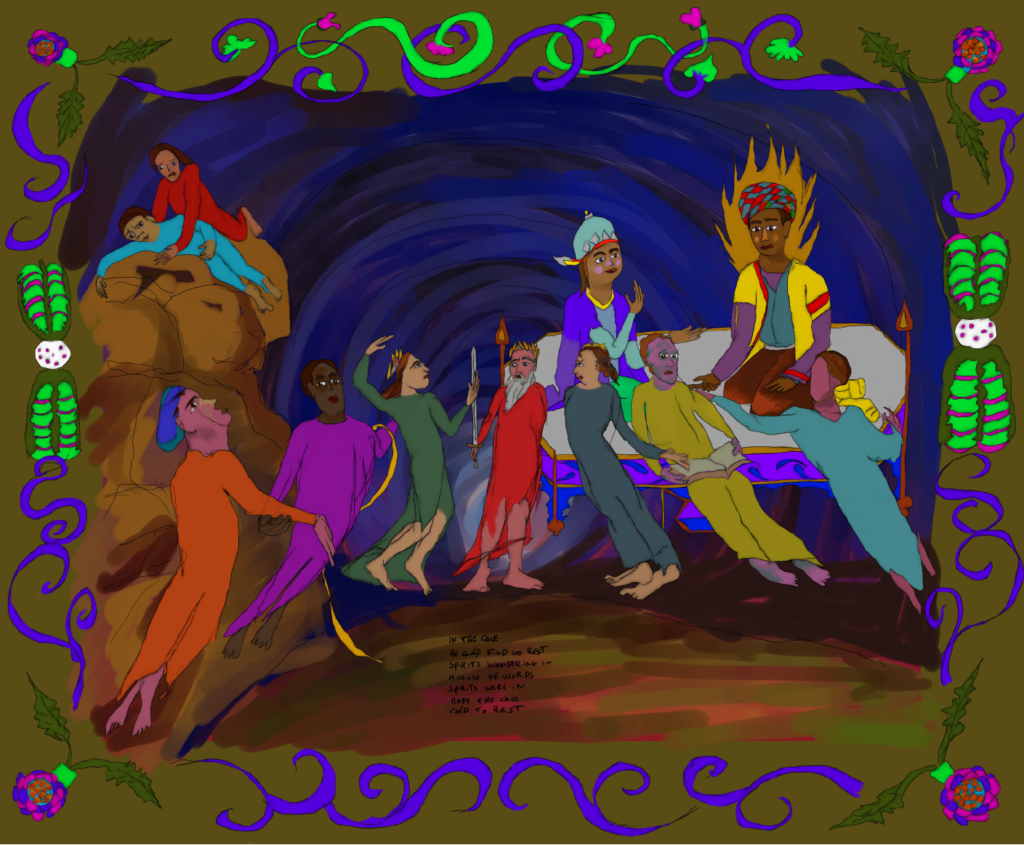

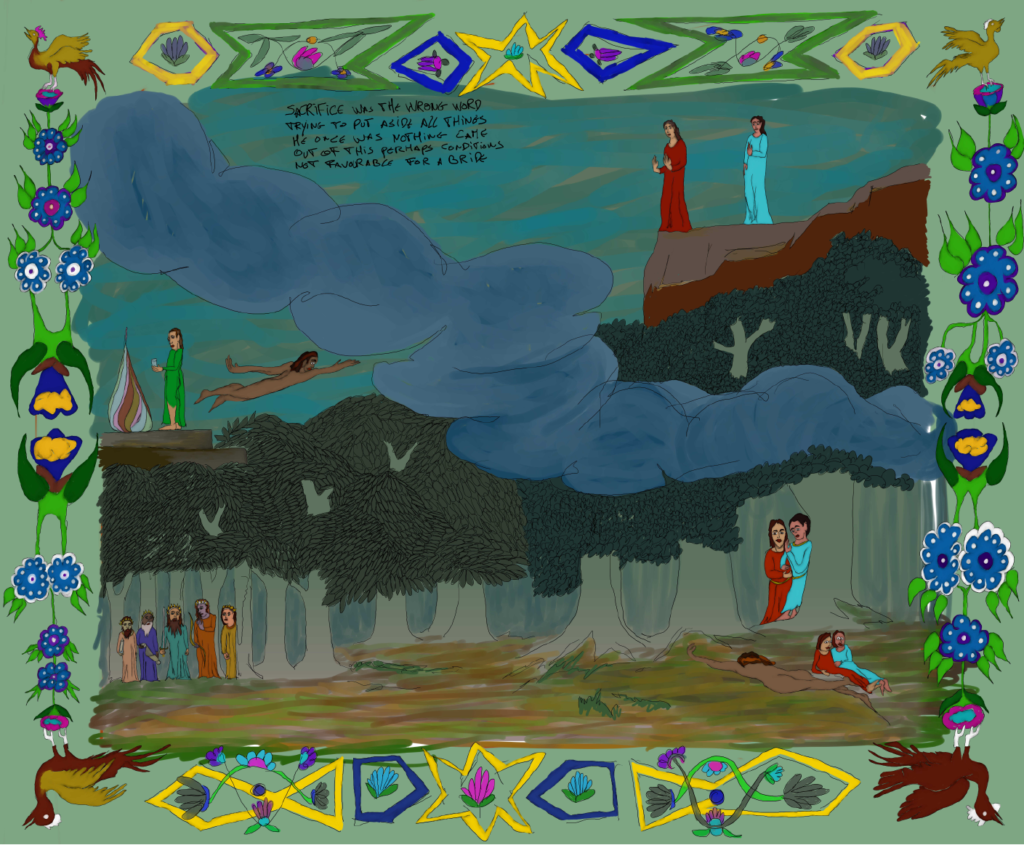

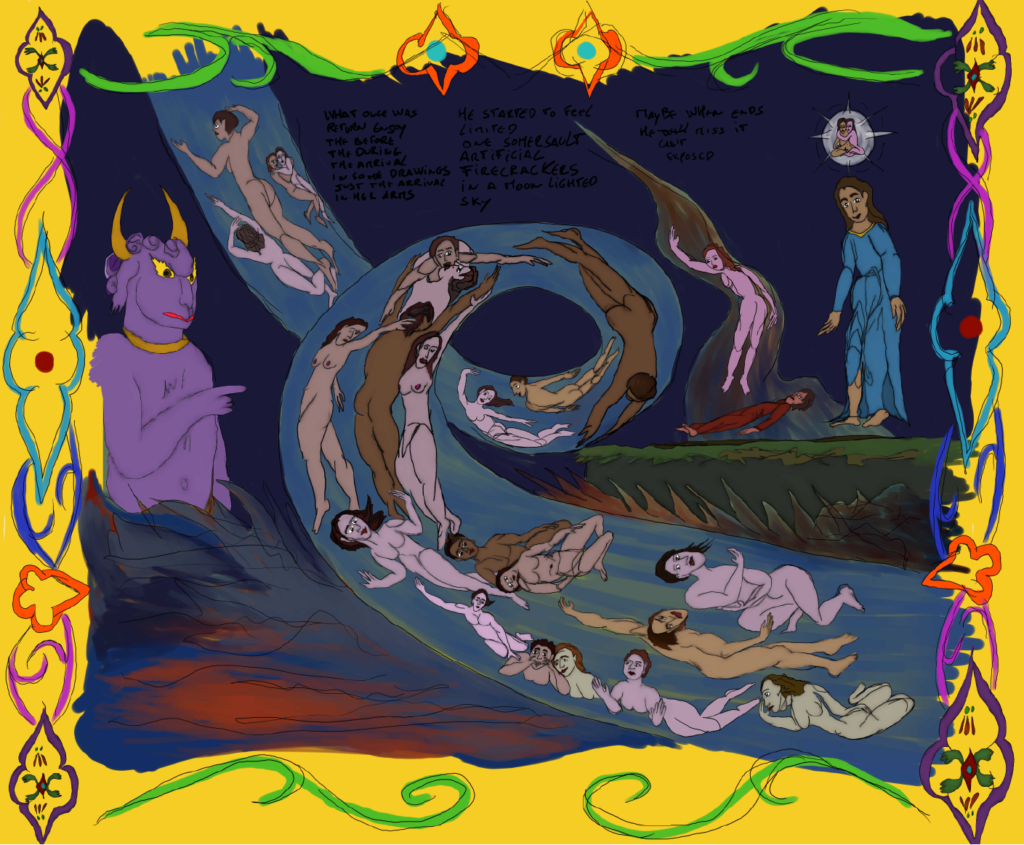

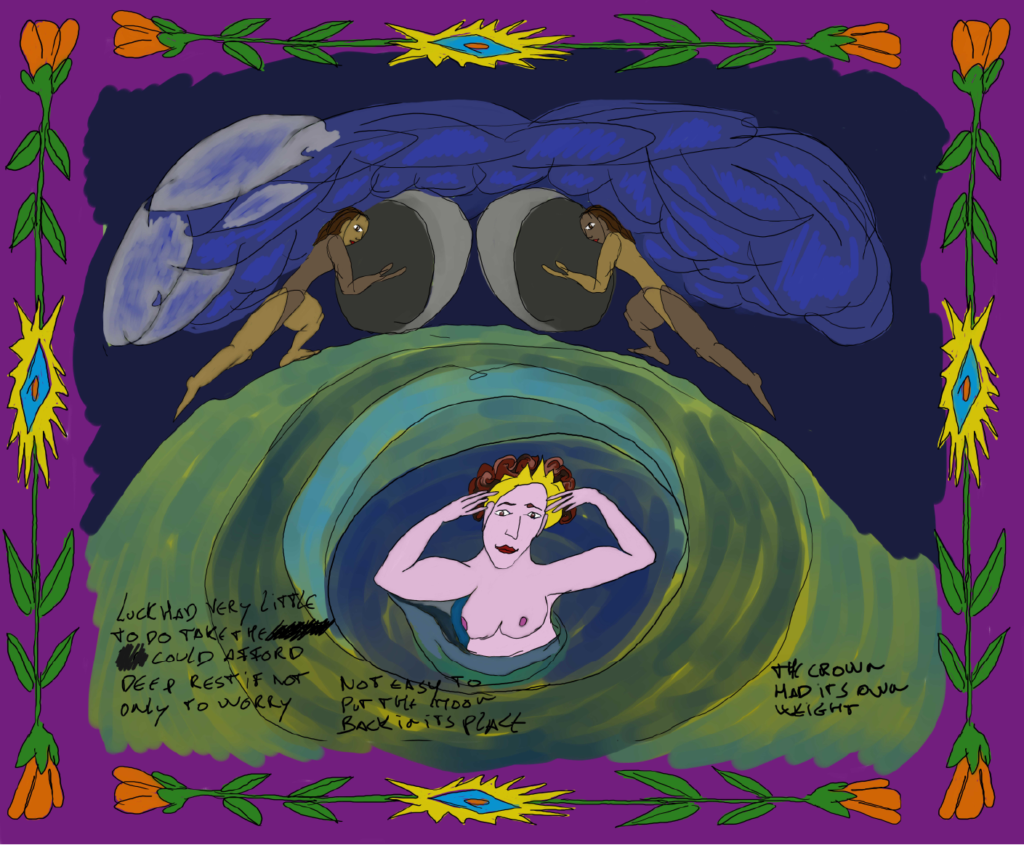

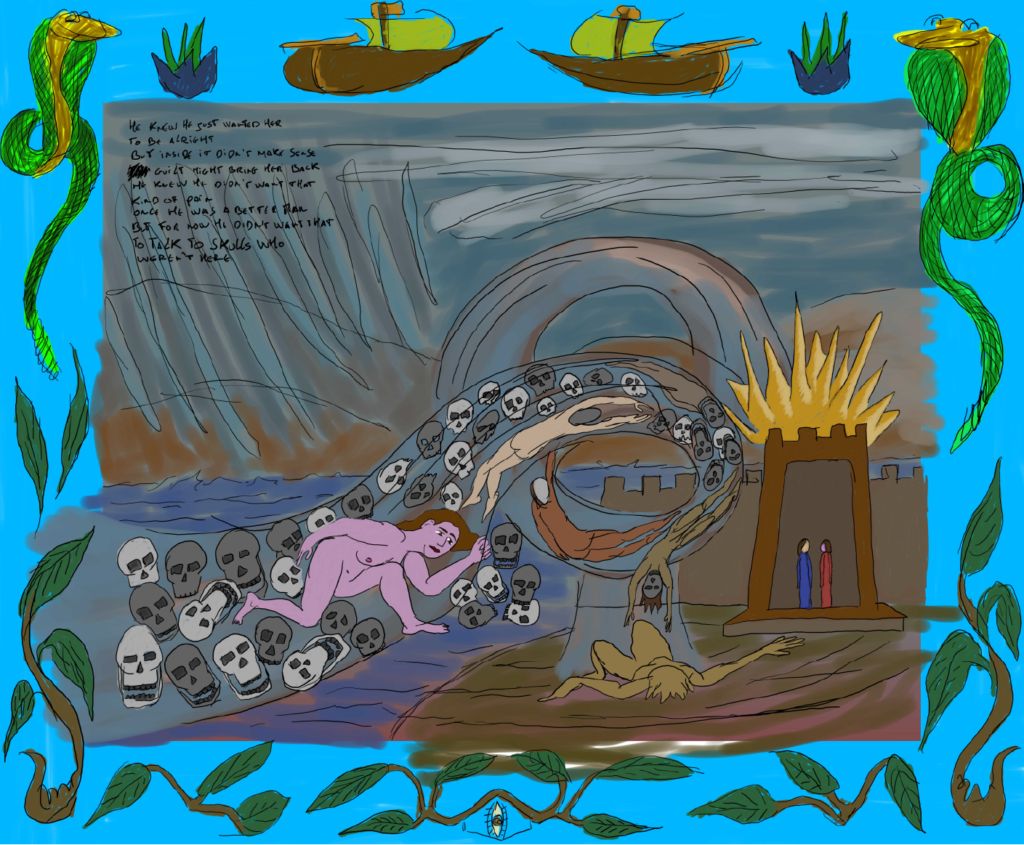

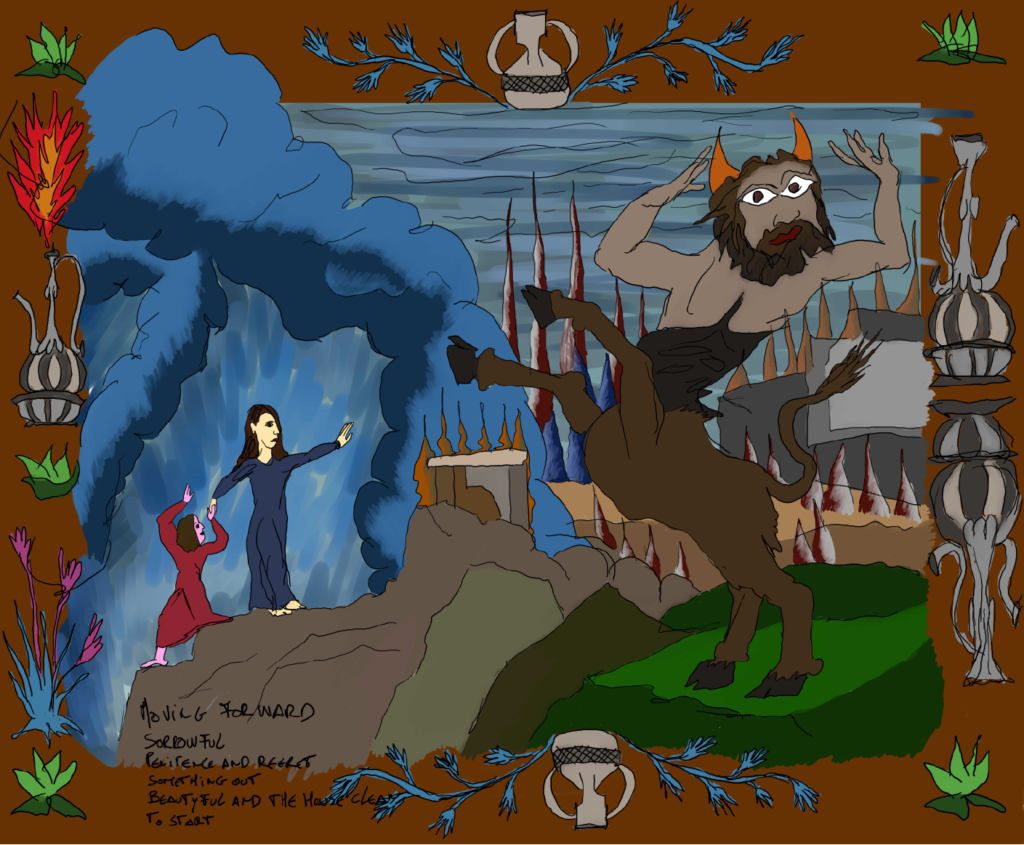

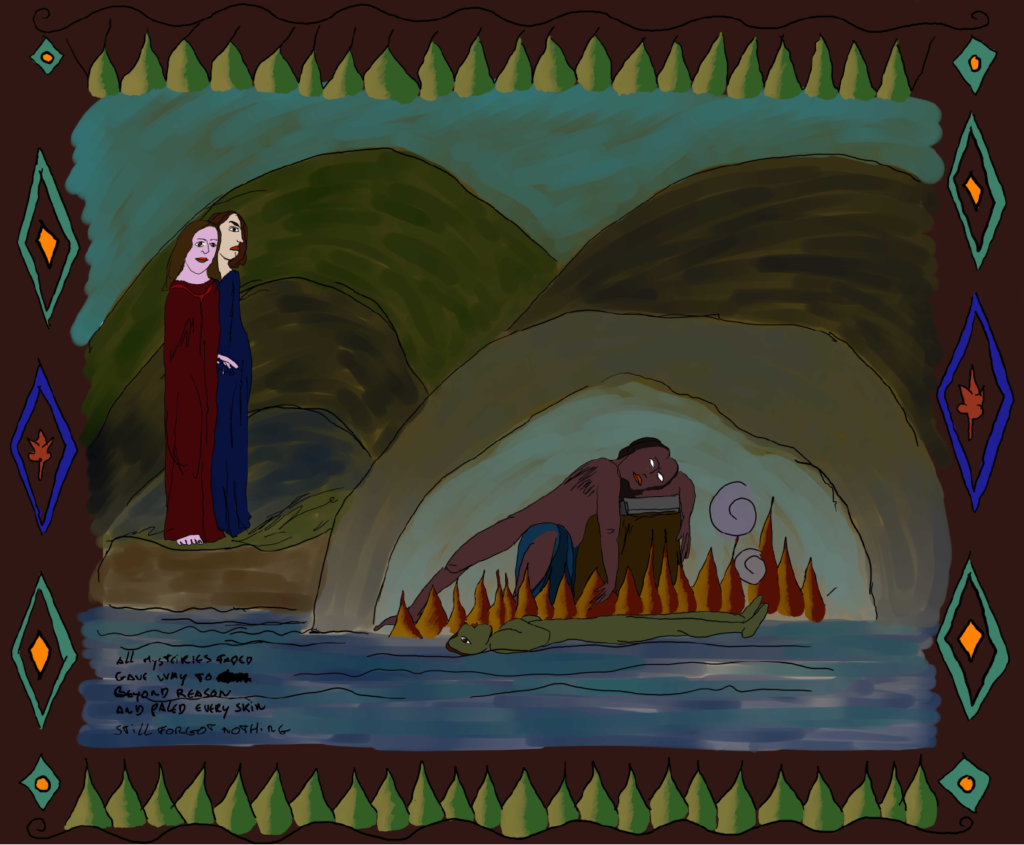

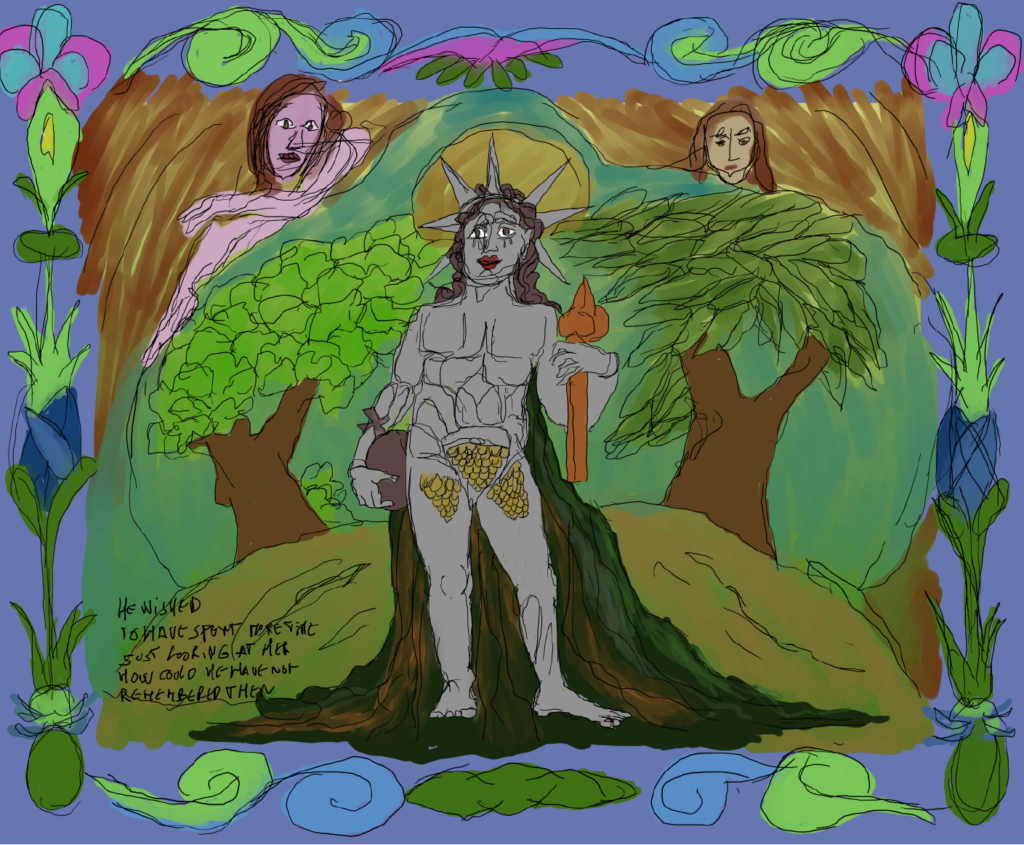

"Feng Ciao" is a conceptual project that reinterprets William Blake's illustrations of Dante's Divine Comedy through the lens of a mid-life crisis. By writing the predominant thoughts directly onto the images I create from these reinterpretations, I add a new layer of meaning to the artwork, creating a dialogue between the images and personal reflections on life's existential turning points. These reflections emerge from the emotional and existential considerations that the reinterpretations provoke, engaging with themes of transformation and self-reflection in the context of a mid-life crisis.

The "Divine Comedy" by Dante Alighieri is more than just a medieval allegory of the afterlife; it is a journey through the depths of human suffering, self-awareness, and ultimate transcendence. Dante's pilgrimage, his descent through Hell (Inferno), his climb through Purgatory (Purgatorio), and his ascent to Paradise (Paradiso), mirrors the profound psychological journey that many individuals experience during a mid-life crisis. As we confront the shadows of our past, the limitations of our present, and the uncertainties of our future, we are compelled to ask fundamental questions about meaning, identity, and purpose. This process of confronting and integrating one's psyche during the middle years of life aligns with several psychological frameworks, particularly the theories of Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud, and Alfred Adler. Through these lenses, Dante’s "Divine Comedy" becomes a powerful metaphor for the individuation process, the resolution of repressed desires, and the quest for a greater sense of belonging and self-actualization.

The mid-life crisis is often seen as a confrontation with the self, a reckoning with the meaning of one's life and the inevitability of mortality. Typically occurring between the ages of 35 and 55, it is a period marked by deep introspection, emotional upheaval, and a desire to reassess life’s goals. This crisis can bring feelings of regret, anxiety, and despair, but it also offers the potential for transformation. Dante’s journey in the "Divine Comedy" can be viewed as a metaphor for this stage of life, where the individual confronts their own limitations (Inferno), seeks redemption and personal growth (Purgatorio), and, ultimately, strives for spiritual enlightenment and self-realization (Paradiso). This process of confronting one's inner demons, reconciling the past, and moving toward a more integrated self mirrors the psychological processes at play in the mid-life crisis.

Inferno: Confronting the Shadows (Freudian Analysis)

In Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, the unconscious is a repository for repressed desires, memories, and fears. These suppressed aspects of the psyche often resurface later in life, leading to what Freud calls "repetition compulsion", the unconscious drive to relive unresolved emotional conflicts from the past. During a mid-life crisis, the individual may be forced to confront these hidden aspects of themselves, much like Dante’s descent into Hell, where he encounters the damned souls suffering the consequences of their own unchecked desires and moral failings.

In Dante's "Inferno", the souls in Hell are trapped by their own sins, sins that are often the result of desires that were either repressed or given free rein without the guidance of ethical awareness. This mirrors Freud’s theory of the "id", the primal part of the psyche that drives unconscious impulses and seeks immediate gratification. During the mid-life crisis, the individual may come face to face with the consequences of unacknowledged desires or unfulfilled goals. The "fires of Hell" in this context are not merely punitive but also illuminate the unresolved conflicts within the unconscious. In confronting these shadows, an individual has the opportunity to bring them into conscious awareness, offering a path to healing.

The individual in a mid-life crisis is not unlike Dante’s own journey into Hell: a descent into the painful and often overwhelming task of self-examination. Like the souls in Hell, the person undergoing a mid-life crisis must confront the consequences of their past choices, be they related to career, relationships, or the neglect of one’s inner life, and reckon with the darkness that these choices have cast upon their present. Yet, just as Dante progresses through Hell rather than staying in it, the individual has the potential to emerge from the unconscious grip of the "id" through self-awareness and catharsis, laying the foundation for a new direction in life.

Purgatorio: The Road to Integration (Jungian Analysis)

Jung’s theory of individuation, the process of integrating the conscious and unconscious parts of the self, offers another lens through which to view the mid-life crisis. Jung believed that this process of self-realization, or coming into wholeness, often takes place during mid-life, when one is confronted with the need to reconcile the disparate aspects of the self that may have been repressed or neglected in youth. In the "Purgatorio", Dante encounters souls who are in the process of purification, working through their flaws and past mistakes in order to achieve spiritual enlightenment. These souls are not damned, but they are undergoing a transformative process of self-realization, trying to come to terms with their past misdeeds.

This journey through Purgatory mirrors the individuation process that many people experience in mid-life. The individual in crisis is asked to revisit past wounds, to acknowledge neglected aspects of their personality, and to integrate these parts into a more balanced, authentic self. Purgatory in Dante’s vision is a place of both suffering and hope, a necessary stage of spiritual growth where the soul is actively purging itself of the excesses and errors of the past. In the mid-life crisis, individuals may find themselves reflecting on past mistakes, unhealed wounds, and unfulfilled dreams. The challenge is to take responsibility for these aspects, recognize their role in shaping the current self, and move forward with a renewed sense of purpose and integrity.

For Jung, this process of individuation requires the person to confront the "Shadow", those aspects of the self that have been repressed or denied. In "Purgatorio", the souls face their own shadows: their pride, greed, and envy, among other vices. But they do so not in despair, but in a spirit of repentance and renewal. Similarly, in the mid-life crisis, the individual must confront their own "Shadow", the unexamined parts of themselves that may have been hidden for years. By embracing these aspects, the person moves toward a more integrated self, one that is both authentic and capable of growth. Dante’s Purgatorio is a metaphor for the transformative potential of mid-life, where the painful confrontation with the past leads to healing and self-integration.

Paradiso: The Quest for Meaning and Self-Actualization (Adlerian Analysis)

Adler’s theory of individual psychology emphasizes the importance of social interest, community, and the striving for significance and self-actualization. According to Adler, mid-life can be a time when the individual questions their sense of purpose in relation to others, asking whether they have lived a life of meaning or simply followed societal expectations. The "Paradiso" in Dante’s "Divine Comedy" represents the ultimate union with the divine, the highest state of spiritual fulfillment. In Dante’s Paradise, the soul experiences an elevated state of awareness, recognizing its connection with the divine order and realizing its full potential.

For Adler, self-actualization is not just about personal achievement, but also about contributing meaningfully to society and living with a sense of purpose. In mid-life, individuals may feel a pull toward greater social engagement or the desire to leave a lasting legacy. Just as Dante ascends through the celestial spheres, ultimately reaching the Beatific Vision in the presence of God, individuals in the midst of a mid-life crisis are often searching for their higher purpose, something beyond material success, beyond personal gain, and beyond ego fulfillment. This desire for greater meaning can prompt a reevaluation of one’s life goals and a reconnection to community and the world.

In this phase of the crisis, there is a shift from "self-centered" striving to a more collective, altruistic sense of purpose, much like Dante’s ultimate vision in Paradise. The realization that life has a broader meaning than individual achievement is part of the Adlerian journey toward social interest and contribution. "Paradiso" symbolizes the potential for self-actualization, but also an understanding of one’s place in the broader scheme of existence, acknowledging both the finite and infinite aspects of life.

Dante’s Journey and the Mid-Life Crisis

Dante’s "Divine Comedy" offers a profound allegory for the psychological journey of the mid-life crisis. The descent into Hell (Inferno) represents the confrontation with the unconscious and repressed desires (Freudian analysis), while the ascent through Purgatory (Purgatorio) embodies the individuation process of self-integration and reconciliation with the "Shadow" (Jungian analysis). Finally, the vision of Paradise (Paradiso) represents the search for meaning, self-actualization, and contribution to the collective good (Adlerian analysis).

In this work, I draw upon these psychological and spiritual frameworks to explore the complex emotional landscape of mid-life. The creative process itself becomes a metaphor for Dante’s journey, a way to navigate the tensions between the unconscious and conscious, the personal and the collective, the finite and the infinite. Like Dante, I seek to offer a visual representation of the psychological and spiritual rebirth that can occur when we confront our anxieties, accept responsibility for our past, and move toward a more integrated and purposeful future. The mid-life crisis, though challenging, is also a powerful opportunity for transformation, an invitation to walk through the realms of self-doubt, fear, and unfulfilled desires, ultimately to emerge as a more whole, authentic self.

Capture

The work invites viewers to confront their own reactions and internal responses to the images, shifting the focus from visual interpretation to the artists psychological process of acknowledging and processing guilt. The reimagined illustrations are layered with subtle, yet profound changes—details that challenge the viewer to question their assumptions, moral judgments, and emotional reactions.

Versão português:

"Feng Ciao" é um projeto conceptual que reinterpreta as ilustrações de William Blake da Divina Comédia de Dante através da lente de uma crise de meia-idade. Ao escrever os pensamentos predominantes diretamente nas imagens que crio a partir dessas reinterpretações, adiciono uma nova camada de significado à obra de arte, criando um diálogo entre as imagens e reflexões pessoais sobre os pontos de viragem existenciais da vida. Essas reflexões surgem das considerações emocionais e existenciais que as reinterpretações provocam, envolvendo temas de transformação e auto-reflexão no contexto de uma crise de meia-idade.

A "Divina Comédia" de Dante Alighieri é mais do que uma alegoria medieval da vida após a morte; é uma jornada através das profundezas do sofrimento humano, da autoconsciência e da transcendência última. A peregrinação de Dante — a sua descida ao Inferno, a sua subida ao Purgatório e a sua ascensão ao Paraíso — reflete a profunda jornada psicológica que muitas pessoas experienciam durante uma crise de meia-idade. À medida que confrontamos as sombras do nosso passado, as limitações do nosso presente e as incertezas do nosso futuro, somos levados a questionar questões fundamentais sobre significado, identidade e propósito. Este processo de confrontar e integrar a psique durante os anos intermédios da vida alinha-se com várias teorias psicológicas, particularmente as de Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud e Alfred Adler. Através dessas lentes, a "Divina Comédia" de Dante torna-se uma poderosa metáfora para o processo de individuação, a resolução dos desejos reprimidos e a busca por um maior sentido de pertencimento e auto-realização.

A crise de meia-idade é frequentemente vista como um confronto com o eu — um acerto de contas com o significado da vida e a inevitabilidade da mortalidade. Normalmente ocorrendo entre os 35 e os 55 anos, é um período marcado por profunda introspecção, turbilhões emocionais e o desejo de reavaliar os objetivos da vida. Esta crise pode trazer sentimentos de arrependimento, ansiedade e desespero, mas também oferece o potencial para transformação. A jornada de Dante na "Divina Comédia" pode ser vista como uma metáfora para esta fase da vida, onde o indivíduo confronta as suas próprias limitações (Inferno), busca redenção e crescimento pessoal (Purgatório) e, finalmente, luta pela iluminação espiritual e auto-realização (Paraíso). Este processo de confrontar os próprios demónios interiores, reconciliar o passado e caminhar para um eu mais integrado reflete os processos psicológicos em jogo na crise de meia-idade.

Inferno: Confrontando as Sombras (Análise Freudiana)

Na teoria psicanalítica de Freud, o inconsciente é um repositório para desejos reprimidos, memórias e medos. Estes aspectos reprimidos da psique muitas vezes ressurgem mais tarde na vida, levando ao que Freud chama de "compulsão à repetição" — o impulso inconsciente de reviver conflitos emocionais não resolvidos do passado. Durante uma crise de meia-idade, o indivíduo pode ser forçado a confrontar estes aspectos ocultos de si mesmo, tal como Dante desce ao Inferno, onde encontra as almas condenadas a sofrer as consequências dos seus próprios desejos incontrolados e falhas morais.

No "Inferno" de Dante, as almas no Inferno estão presas pelos seus próprios pecados — pecados que são frequentemente o resultado de desejos que foram ou reprimidos ou deixados sem controlo, sem a orientação da consciência ética. Isto reflete a teoria de Freud do "id", a parte primal da psique que impulsiona os instintos inconscientes e busca gratificação imediata. Durante a crise de meia-idade, o indivíduo pode confrontar as consequências de desejos não reconhecidos ou objetivos não cumpridos. Os "fogo do Inferno", neste contexto, não são apenas punitivos, mas também iluminam os conflitos não resolvidos no inconsciente. Ao confrontar essas sombras, o indivíduo tem a oportunidade de trazê-las à consciência, oferecendo um caminho para a cura.

O indivíduo numa crise de meia-idade não é diferente da jornada de Dante no Inferno: uma descida à tarefa dolorosa e muitas vezes avassaladora de auto-exame. Tal como as almas no Inferno, a pessoa em crise de meia-idade deve confrontar as consequências das suas escolhas passadas — sejam elas relacionadas com a carreira, relacionamentos ou o descuido da vida interior — e lidar com a escuridão que essas escolhas lançaram sobre o presente. No entanto, assim como Dante avança através do Inferno, em vez de ficar nele, o indivíduo tem o potencial de emergir da influência inconsciente do "id" através da auto-consciência e catarses, estabelecendo as bases para uma nova direção na vida.

Purgatório: O Caminho para a Integração (Análise Junguiana)

A teoria de individuação de Jung — o processo de integração das partes consciente e inconsciente do eu — oferece uma outra lente através da qual podemos ver a crise de meia-idade. Jung acreditava que esse processo de auto-realização, ou de alcançar a totalidade, muitas vezes acontece na meia-idade, quando o indivíduo se vê confrontado com a necessidade de reconciliar os aspetos díspares do eu que podem ter sido reprimidos ou negligenciados na juventude. No "Purgatório", Dante encontra almas que estão no processo de purificação, trabalhando através das suas falhas e erros passados para alcançar a iluminação espiritual. Estas almas não estão condenadas, mas estão a passar por um processo transformador de auto-realização, tentando aceitar os seus erros passados.

Esta jornada pelo Purgatório reflete o processo de individuação que muitas pessoas experienciam na meia-idade. O indivíduo em crise é desafiado a revisitar feridas passadas, reconhecer os aspetos negligenciados da sua personalidade e integrar essas partes num eu mais equilibrado e autêntico. O Purgatório na visão de Dante é um lugar de sofrimento e esperança — uma etapa necessária de crescimento espiritual onde a alma está a purgar-se dos excessos e erros do passado. Na crise de meia-idade, os indivíduos podem encontrar-se a refletir sobre erros passados, feridas não curadas e sonhos não realizados. O desafio é assumir a responsabilidade por esses aspetos, reconhecer o seu papel na formação do eu atual e avançar com um renovado sentido de propósito e integridade.

Para Jung, este processo de individuação exige que a pessoa confronte a "Sombra" — aqueles aspetos do eu que foram reprimidos ou negados. No "Purgatório", as almas enfrentam as suas próprias sombras: o orgulho, a ganância e a inveja, entre outros vícios. Mas fazem-no não com desespero, mas com um espírito de arrependimento e renovação. Da mesma forma, na crise de meia-idade, o indivíduo deve confrontar a sua própria "Sombra" — as partes não examinadas de si que podem ter sido escondidas durante anos. Ao abraçar esses aspetos, a pessoa avança para um eu mais integrado, que é autêntico e capaz de crescimento. O "Purgatório" de Dante é uma metáfora para o potencial transformador da meia-idade, onde o confronto doloroso com o passado leva à cura e à auto-integração.

Paraíso: A Busca pelo Significado e Auto-Realização (Análise Adleriana)

A teoria da psicologia individual de Adler enfatiza a importância do interesse social, da comunidade e do esforço por significância e auto-realização. Segundo Adler, a meia-idade pode ser uma altura em que o indivíduo questiona o seu sentido de propósito em relação aos outros, perguntando-se se viveu uma vida de significado ou se simplesmente seguiu as expectativas sociais. O "Paraíso" na "Divina Comédia" de Dante representa a união final com o divino, o mais alto estado de realização espiritual. No Paraíso de Dante, a alma experimenta um estado elevado de consciência, reconhecendo a sua conexão com a ordem divina e realizando o seu pleno potencial.

Para Adler, a auto-realização não se trata apenas de conquista pessoal, mas também de contribuir de forma significativa para a sociedade e viver com um sentido de propósito. Na meia-idade, os indivíduos podem sentir-se atraídos para um maior envolvimento social ou o desejo de deixar um legado duradouro. Tal como Dante ascende pelas esferas celestes, alcançando finalmente a Visão Beatífica na presença de Deus, os indivíduos no meio de uma crise de meia-idade estão frequentemente à procura do seu propósito superior — algo além do sucesso material, além do ganho pessoal e além da realização do ego. Este desejo por um significado maior pode levar à reavaliação dos objetivos da vida e à reconexão com a comunidade e o mundo.

Nesta fase da crise, há uma mudança do esforço "centrado no eu" para um propósito mais coletivo e altruísta — muito como a visão final de Dante no Paraíso. A percepção de que a vida tem um significado mais amplo do que a realização individual faz parte da jornada adleriana rumo ao interesse social e à contribuição. O "Paraíso" simboliza o potencial de auto-realização, mas também a compreensão do lugar do indivíduo no plano mais amplo da existência, reconhecendo os aspetos finitos e infinitos da vida.

A Jornada de Dante e a Crise de Meia-Idade

A "Divina Comédia" de Dante oferece uma alegoria profunda para a jornada psicológica da crise de meia-idade. A descida ao Inferno (Inferno) representa o confronto com o inconsciente e os desejos reprimidos (análise freudiana), enquanto a ascensão pelo Purgatório (Purgatório) incorpora o processo de individuação da auto-integração e reconciliação com a "Sombra" (análise junguiana). Finalmente, a visão do Paraíso (Paraíso) representa a busca por significado, auto-realização e contribuição para o bem coletivo (análise adleriana).

Neste trabalho, recorro a esses frameworks psicológicos e espirituais para explorar a complexa paisagem emocional da meia-idade. O processo criativo em si torna-se uma metáfora para a jornada de Dante — uma forma de navegar pelas tensões entre o inconsciente e o consciente, o pessoal e o coletivo, o finito e o infinito. Tal como Dante, procuro oferecer uma representação visual do renascimento psicológico e espiritual que pode ocorrer quando confrontamos as nossas ansiedades, aceitamos a responsabilidade pelo nosso passado e avançamos para um futuro mais integrado e com propósito. A crise de meia-idade, embora desafiadora, é também uma poderosa oportunidade para transformação — um convite a atravessar os reinos da dúvida, medo e desejos não cumpridos, para, finalmente, emergir como um eu mais completo e autêntico.