Paraphrased transcript of my interview, conducted by Luana Viegas at the time of the exhibition "A wagon full of devils and the lovers strife" 2024

Luana Viegas: Have you always been an artist, or what led you to become one?

Luis Miguel de Matos: Yes, I am a visual artist. It’s a bit hard to define exactly when, but I earned a degree in Fine Arts from the University of Lisbon and graduated in 2009. I started painting while I was still a student at the Instituto Superior Técnico in Technological Physics Engineering. I took a private painting course run by an art gallery, and that's where my interest began. At first, it was a very romanticized ideal of what art and painting were. Later, at university, I deepened my understanding of the potential of art and the contemporary role of the visual artist. Since I began that private painting course, I’ve been fully dedicated to the visual arts, and since university, it has always been the central practice in my life.

LV: What are or have been your inspirations? What shapes your artistic language?

LM: My artistic language is diverse, it's multidisciplinary. Gradually, I discovered my own artistic path—I explored installation, photography, drawing, painting. I'm very influenced by art history, symbolism, and various symbolic interpretations of images. My projects so far are deeply personal, very autobiographical. Even though I try to include community engagement—working in communities, on various different projects, involving people, some of whom have artistic ambitions and others who don’t—I try to involve them in the projects I create.

My language has gradually become more refined in terms of interpretation. I’ve developed more awareness and responsibility regarding what I create, the images I put into the world, the objects I make, and their interpretative and symbolic consequences. My awareness about the interpretation and symbolism of images has grown. This project marks the beginning of a more individual, singular path. It’s very much tied to psychology, to how I interpret my own personal experiences. There’s always a confessional theme in the work.

There’s always a search for redemption, a desire to find in the act of making and telling something that redeems, that consoles the mistakes made throughout life, the less positive experiences, the decisions taken. It's a way to redeem myself, my work, and to negotiate my role in society.

LV: Along this journey, could you tell us a bit about some challenges, both professional and personal—any difficulties you faced and overcame to get here? Is this new stage, with this exhibition, something you want to express from the inside out?

LM: Yes, there was a time when I conceptualized art in the third person. I told imaginary stories that didn’t necessarily relate to my personal experience. Although, looking closer, there’s always a connection to individuality, to personal paths and experiences. But in this exhibition, there’s a real focus on a very beautiful but very difficult personal experience. I approach the theme of love. The difficulty here was exposing my own intimacy—how far was I willing to go in deeply exploring my personal experiences? How far was I willing to tell the story in a real, truthful way?

The process was hard—it was very emotionally cathartic. Many of the drawings evoked memories that weren’t so positive and stirred up strong emotions. It was about accepting suffering and trying to observe the suffering caused impartially, from a detached perspective that allowed me to feel the emotions but maintain some distance. That was a challenge. Then came the nerves of the exhibition and the expectations. People interpret things in their own way; the artist creates the object and the narrative, but the works take on a life of their own, and people interpret them through their own context and circumstances.

As the exhibition approached, I felt nervous but also hoped I could gain more emotional distance from the works. And that happened. Once John started handling the works, placing them on the wall, they lost a lot of the emotional and personal charge they held for me. As people came in and began relating to the works—the exhibition has many pieces—the story became diluted. It stopped being just the story I told to myself and became a story I shared with others, one they could interpret in their own way.

There’s also a challenge because I create images from scratch. These are interpretations, and I have references, but they come from emotional states that didn’t have images before. People live in a world saturated with images, so it’s hard for them to recognize the originality or identity of the work outside that context. But for me, the work strengthened my psyche—it helped me symbolize fragile elements I didn’t want to see or confront, solidify them, and understand my vulnerabilities. It also helped me recognize strengths that memory—and sometimes bitterness or loss—tends to contaminate. By symbolizing these emotions, I create original images that feel very powerful to me, even though they may become diluted in our image-saturated world where each person has their own visual dictionary, bookstore, library.

For me, these are moments of creation and transformation, turning the abstract into the concrete. But people see and interpret these images differently. Letting go of the expectation that people would see the works as I do was a challenge—and realizing that the emotional intensity I feel gets diluted. And in that process, I also realized I’m not as important as I thought. The works aren’t as significant to others as they are to me, even though, for me, they were deeply meaningful.

LV: In our last conversation, you came across as a very empathetic, altruistic person. What led you to this more attentive way of seeing others? How has it helped you grow personally?

LM: I’ve done a lot of volunteer work. I volunteered in Italy with people with disabilities. I volunteered with children in Nepal and in South America, in Peru. Now I work with seniors. This has to do with a personal challenge of sublimating pain. I take very difficult episodes from my life and try to sublimate them by helping others.

I’m fortunate to have a quality of life that allows me to do this, beyond all the excitement and adventure that volunteering abroad brings—getting to know new cultures, people, and situations. After going through difficult periods in my life, I decided the best way to sublimate pain was to collaborate, to help others, rather than drown in pain or become resentful. I learned this a lot through painting. My early paintings during school and university were deeply internal, representing pain, misalignment, a major existential crisis that lasted for years. But after an Erasmus stay in Finland, my paintings became much cleaner and more empowering—less a suffering representation of reality.

I carried that shift from painting into a more social context. Instead of focusing on my own burdens and struggles, I found that a stronger way to process and work through my fragilities was by trying to have a positive impact on others’ lives. It’s a way of sublimating pain and overcoming it—creating milestones that make me think, “That was hard, it was painful, but it was worth it because it led to this positive outcome.” A situation that’s not just beautiful but constructive—based on respect and mutual acceptance. The projects I’ve done—with people with disabilities, seniors, or children—often culminate in a creative ending: an installation, an event. That’s a meaningful outcome. From the first experience, especially with people with disabilities, I saw the results. I saw that my pain and sorrow were truly transformed in this alchemy—taking the most decayed, difficult material and turning it into something positive, a positive experience, a positive memory.

LV: You said earlier that most of life consists of suffering. Is that your general worldview or just in specific aspects?

LM: I have a fairly pessimistic view of the world. I believe suffering is a major component of life, and as we grow older, abandonment and loss become facts of life. Life follows a trajectory that, in its first half, is ascending—developing, gaining experiences, relationships, skills. Eventually, it’s a declining path, with losses, fragility, vulnerability, a decline in ability and aptitude.

I see life in that way—a view that closely aligns with Buddhism: that life is suffering. But unlike Buddhism, I don’t so easily find relief from suffering in inner realization. I believe more in relief through active engagement—moving outward, seeking consolation from loss and pain by creating something, by doing good. By trying to remove others’ suffering, being a positive force, sublimating not only our own pain but also that of others’.

LV: Can you tell us a bit about your next exhibition—what it’s about and what we’ll find there?

LM: My next exhibition is also very personal. It’s tied to closing a cycle that began during the pandemic. During that time, I had several intentions I wanted to pursue—and this exhibition is one of them. It’s called Dreams and Mischief (Sonhos e Malandrices). These are dreams I had during the lockdowns, when I noticed my dreams became much more vivid.

There’s a view in shamanism that dreams are not merely products of the unconscious, as Jungian psychology might say, but something more—they're glimpses of the metaphysical. They’re not just narratives the unconscious creates randomly. They have a guiding role in our reality. They’re places where we process things that impact our consciousness.

This is very personal because the works are based on my dreams. Once again, it’s a way of creating strong images tied to my unconscious vulnerabilities and strengths—solidifying experiences lived in the dream world. Some represent overcoming. Others are more labyrinthine and evoke challenges I haven’t yet overcome—images of disorientation or confusion. But the aim is to create stories from the dream world. For me, many things I paint end up becoming reality later. I don’t know if it’s just the power of suggestion—because we act on what we imagine—but I also believe, more in line with Jung, that certain experiences are universal and cyclical.

So, by reflecting on my dreams and my unconscious, I believe I gain tools and strength to face situations in my life—and perhaps even get a glimpse of what’s to come.

LV: Would you like to leave a message for emerging artists or anyone who loves art and wants to express themselves through it? What advice would you give?

LM: My artistic path is quite unique, but above all, what I think is most important is creating some distance—some distance between what you make and who you are. I believe art can be a priority and play a central role in life. But many ideas we form when trying to become professional artists can obstruct the work.

I think it’s more important to be a person first. I made that mistake—art took over my life. Every action, every relationship, every experience was directed at becoming a professional artist. But, for instance, placing monetary pressure on work reduces its quality and freedom. So, my biggest advice is: achieve financial stability first. That way, you can develop your art without such a heavy burden, which also improves how you relate to the public. It’s much more valuable for the work to be a genuine act of sharing, without interests, than to be weighed down by collectors and buyers.

In terms of artistic practice itself: explore. Look at references. Study other painters. Know art history well. Understand that the concept of beauty is an aesthetic and philosophical question. Technical aspects—of painting or drawing—are just that: technical. Try to separate these things and avoid mental models like “I want to paint like this” or “I wish my work looked like that.” Try to explore.

Drawing is a learned skill. Technique comes with practice. It’s an adventure. You start in one place and might end up somewhere completely different. And then ask: what role does creativity or art truly play in your life? Don’t do what I did—blood, sweat, and tears for your artistic work. Artistic work has its place, but over-identifying as an artist can be counterproductive in many aspects of life. Life is much more colorful and diverse than just artistic aspirations. That’s a piece of advice based on experience—because there really is life beyond art, and it took me a while to realize that.

LV: I think not just personally, but in general, what is it like to be an artist in Lagos? Because Lagos is a smaller city, a tourist city, but at the same time we see that it’s very much focused in other directions. I know you’ve also taught in schools. What is that interaction with young people like, and how do you see that area here?

LM: Well, Lagos is a difficult context in which to be an artist. It has many advantages because it offers a good quality of life — much better when compared to living in Lisbon or Porto. Here, again, it has to do with one’s ambitions. From the moment the economic aspect is separated from your artistic practice — which is my case — being an artist becomes easier, because essentially the focus is on creation. Whether that means creating opportunity or creating diversity.

For example, I didn’t work with young people, I worked with children, but the goal there was very simple. The goal was to develop creative potential in the children. Later, to develop certain manual skills, but above all, for them to have examples to look up to — painters, artists — so they could have a richer inner life. Even though the children were quite young, it’s important to instill these ideals from an early age, these models that allow us to have more freedom of choice, more freedom in our options.

And now I’ve worked with seniors. I don’t really know what my life is going to be like. I don’t really know what it means to be an artist in Lagos. I’ve been here more consistently, more solidly, for a few years now. Being an artist, in general, already has many challenges.

So, being an artist in Lagos. For me, right now, it has a lot to do with access. There’s been work done over these past three years to gain access. I waited a year to have an exhibition here at the gallery — to gain access, to be able to present my work. I waited quite a long time to get access to the Cultural Center, whether to present the work I developed with the seniors, or now for my solo exhibition.

My main concern was to have access, to have the necessary infrastructure to present the work to the public. That’s kind of how I’ve been seeing my artistic path lately. It has to do with this connection to communities and with more social, community-based work. It has to do with trying to elevate and invigorate, as best I can, the situations I find myself in.

Here in the gallery, it was about doing the best work I could plan for that space, because I think it's necessary for us, within our inner energy and the perspective we gain over the years — and I’ve had quite a long journey abroad — it’s important, when there’s some consistency in what we’ve achieved, to develop the work and the act of creation with as much vitality as possible. In such a way that the people who see the work, and other artists who see the projects and how you carried them out, find them suggestive — that they suggest solutions, suggest paths that might not be so clear.

This came up a lot during the pandemic. It was a generalized situation where, if we don’t have events or movements, people stagnate and regress. So it’s important to create, within the possible dynamics, goals that are challenging and that leave for people who view the work a sense of what is possible.

If there aren’t these ideals, these examples to follow — I myself follow them. I have colleagues who are examples to follow, people who have reached certain milestones, whether intellectual — in terms of interpretation that opens my eyes — or more social milestones, who have reached certain positions or taken part in certain events, and that gives me a sense of possibility and allows me to imagine and work towards achieving similar things.

And I see, in my dynamic of being an artist in Lagos, a bit of that in the work I do as a teacher and in the work I do as a visual artist. It’s a bit about trying, with my resources, to create a situation that is as competent and as vital as possible so that people can see the possible paths. From the most specific — like drawing and manual activity — to the more general — like the installation and the possibilities, for example, of dissemination. For people to realize that there are possible paths, that there are things that can be done, that life is vital if we ourselves have the vitality to contribute, to improve, to develop.

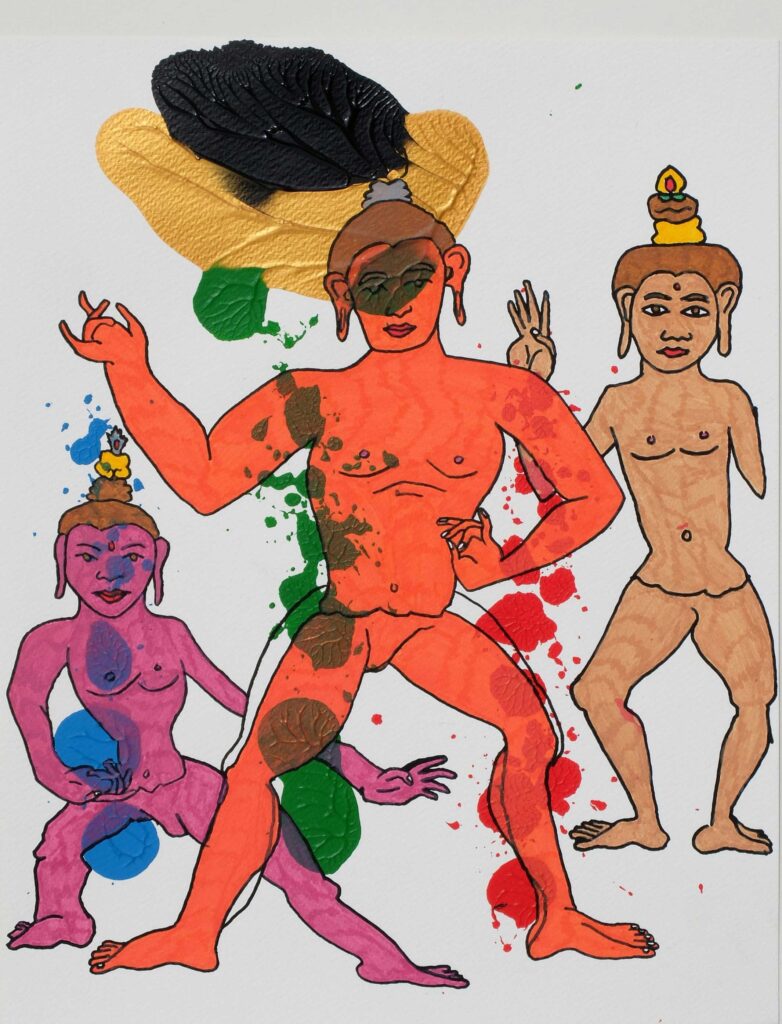

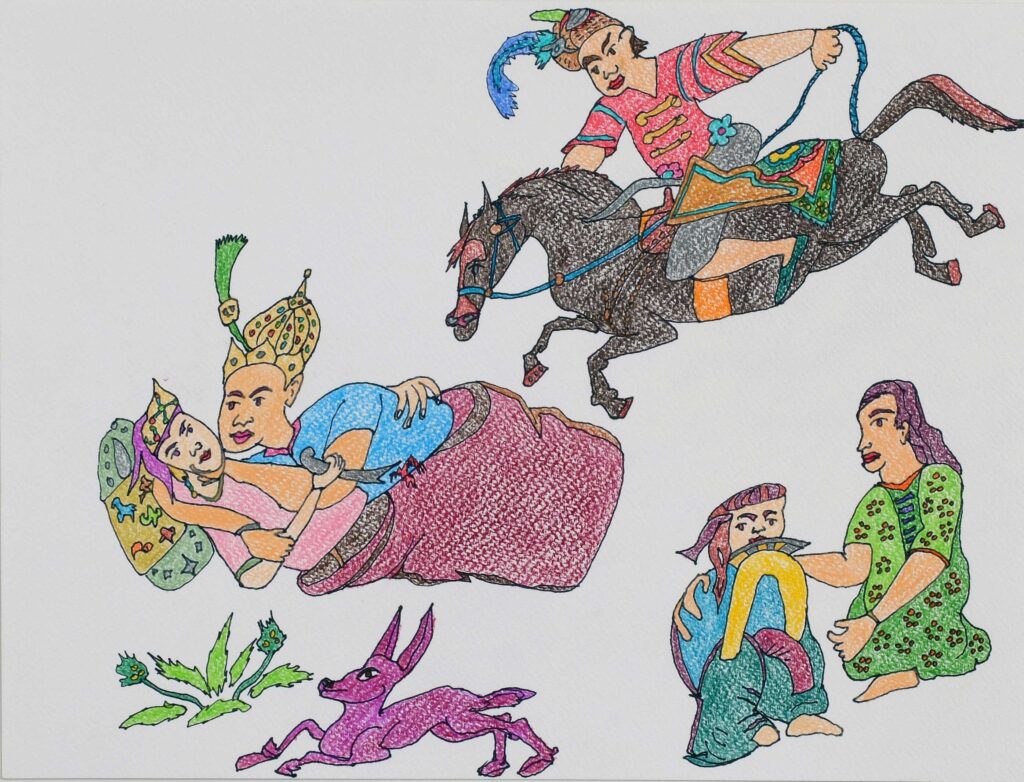

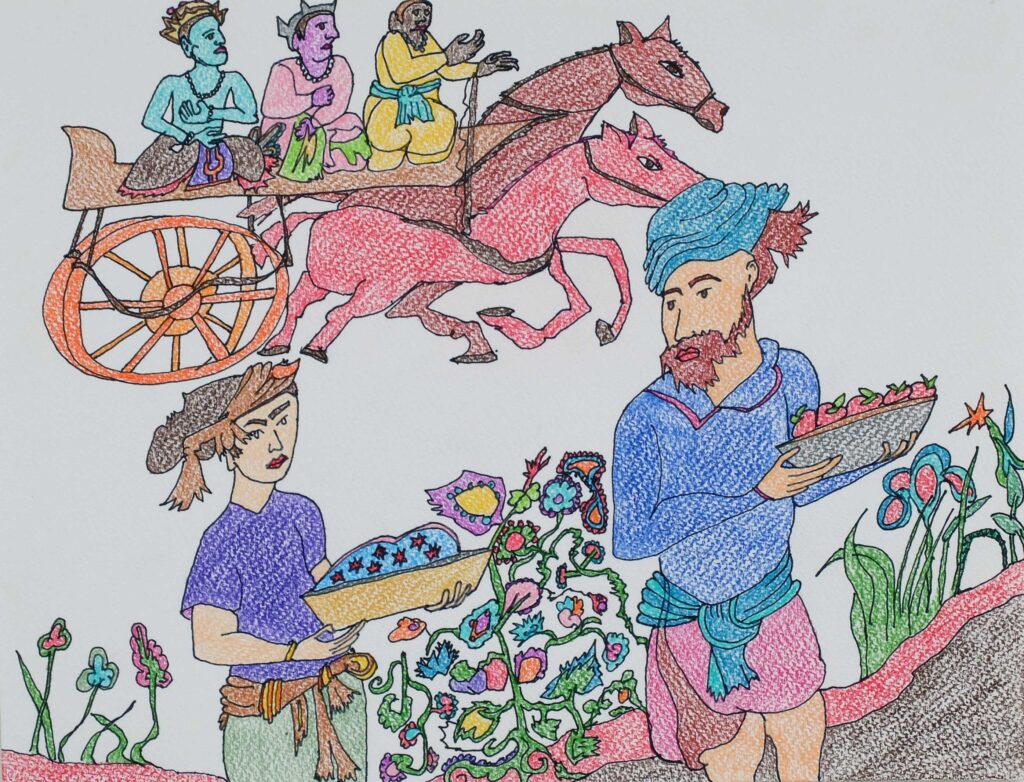

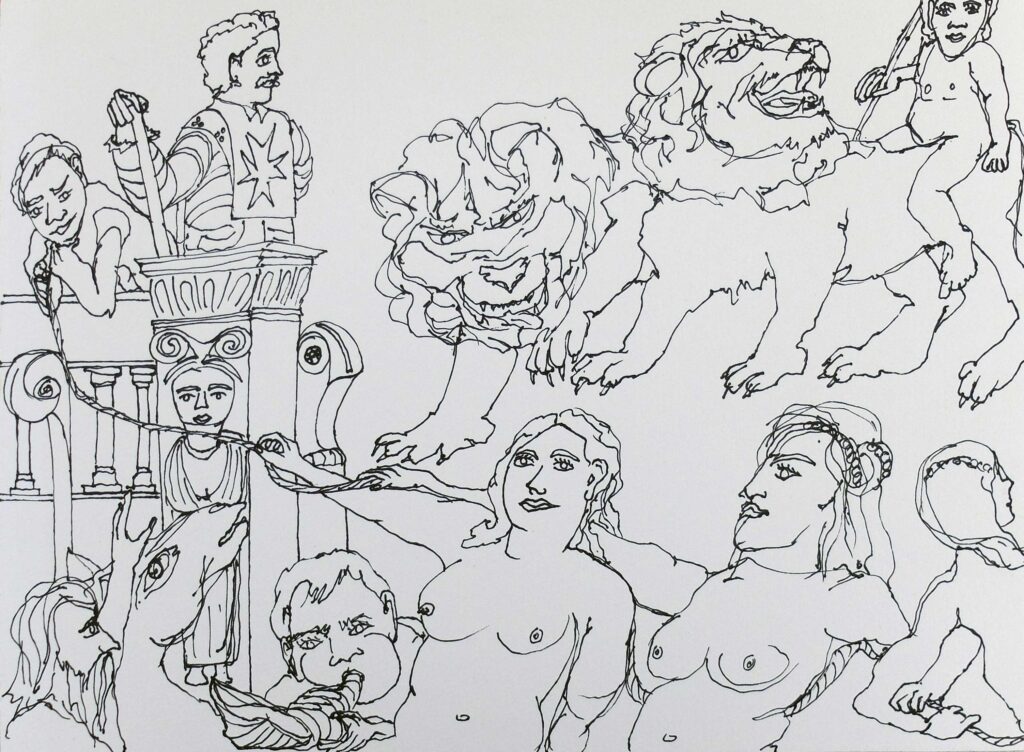

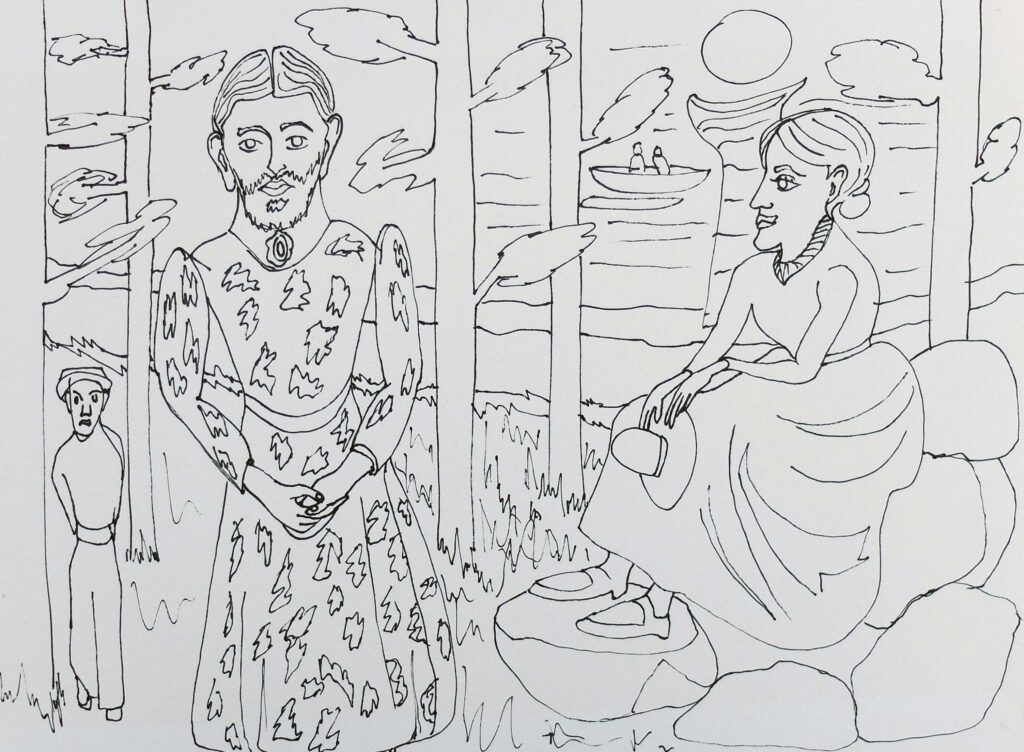

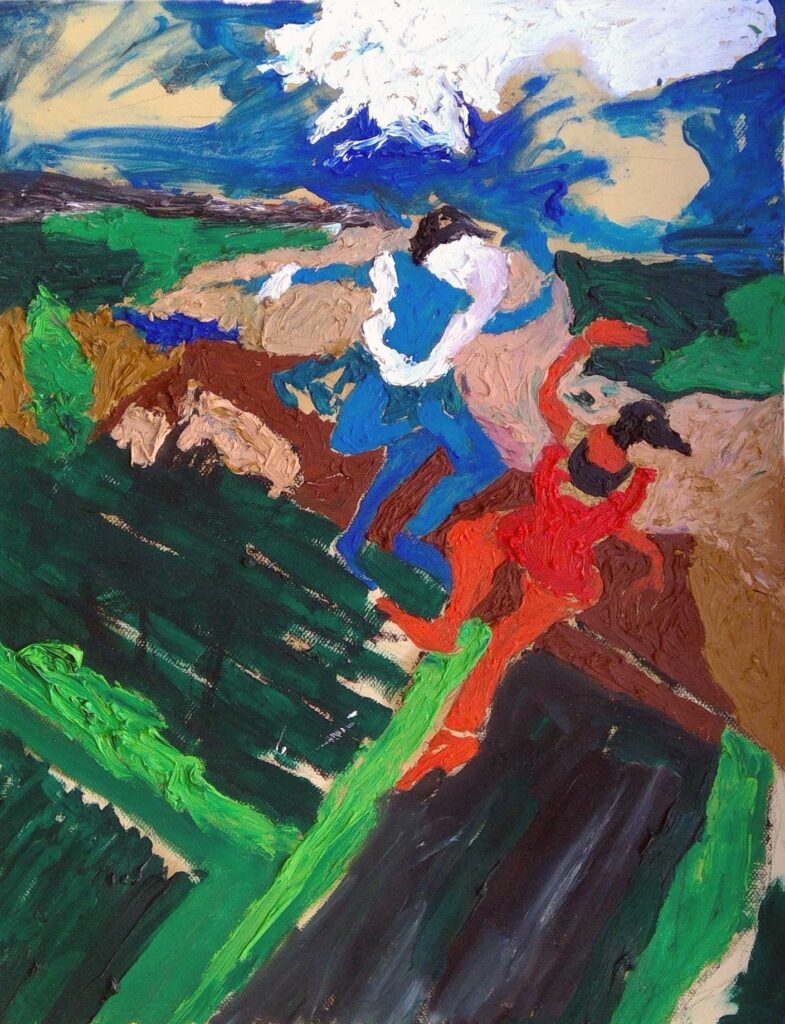

This work is the mythologization of a love story, tender, chaotic, and larger than life, born from my real relationships and inner journeys. It’s a deeply personal reflection shaped through Jungian analysis, where every encounter with love became an initiation, every heartbreak a portal. The drawings are layered with cultural references, myth, pop culture, symbols, because love has always felt like something ancient playing out through modern faces.

At its heart, this work also tells the story of a war, not metaphorical, but real, fought and won in the collective unconscious. I’ve always had a strange sensitivity, a way of touching that deeper field where we’re all connected. In times of intense emotion, especially in love, I found I could move things there, clear patterns, dissolve old myths, plant new seeds. These drawings are traces of that process. They’re not just art, they’re artifacts from a psychic battleground where something was shifted.

This is my way of mythologizing love, not to escape reality, but to show how it pulses beneath it. Each image is a spell, a memory, and a blueprint for how the inner and outer worlds can change each other.

Versão português:

Esta obra é a mitologização de uma história de amor, terna, caótica e maior do que a vida, nascida das minhas relações reais e das minhas jornadas interiores. É uma reflexão profundamente pessoal moldada através da análise junguiana, onde cada encontro com o amor se tornou uma iniciação, cada desgosto um portal. Os desenhos estão impregnados de referências culturais, mitologia, cultura pop e símbolos, porque o amor sempre me pareceu algo ancestral a manifestar-se através de rostos modernos.

No seu âmago, esta obra conta também a história de uma guerra não metafórica, mas real, travada e vencida no inconsciente colectivo. Sempre tive uma sensibilidade estranha, uma forma de tocar nesse campo mais profundo onde todos estamos ligados. Em momentos de emoção intensa, especialmente no amor, descobri que conseguia mover coisas nesse lugar, limpar padrões, dissolver mitos antigos, semear novas possibilidades. Estes desenhos são vestígios desse processo. Não são apenas arte, são artefactos de um campo de batalha psíquico onde algo foi transformado.

Esta é a minha forma de mitologizar o amor, não para escapar à realidade, mas para mostrar como ele pulsa por baixo dela. Cada imagem é um feitiço, uma memória e um mapa de como os mundos interior e exterior podem transformar-se mutuamente.